[1] Methods for diagnosis of neurodegenerative brain diseases

[2]Field of the invention

[3]The present application relates to the field of human genetics, particularly in relation to the field of neurodegenerative brain diseases. Specifically, the present invention relates to methods and materials to detect human neurodegenerative brain diseases, more particularly dementia (Alzheimer's disease (AD), Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), dementia with Lewy bodies dementia (DLB)), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson's disease (PD). Specifically envisaged diseases include AD, FTLD and diseases of the FTLD/ALS spectrum. Provided herein are diagnostic assays for the detection of neurodegenerative brain diseases, kits for performing these assays, and methods to treat these diseases.

[5] Neurodegenerative brain diseases (NBD) are a group of disorders characterized by a progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, including death of neurons. Many neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson's disease (PD) occur as a result of neurodegenerative processes. Many of these diseases share similarities, which relate these diseases to one another on a sub-cellular level. For instance, different neurodegenerative disorders feature atypical protein assemblies as well as induced cell death. More specifically, it is known that the clinical presentations of AD, FTLD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) overlap considerably, despite the different pathologic processes (Piquet et al., 2009). Likewise, genetics and pathology support the idea of a continuum between frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and ALS (Lillo and Hodges, 2009; Sieben et al., 2012; Van Langenhove et al., 2012). Furthermore, although several highly penetrant genetic variations (= causative mutations) and more common genetic variations that act as genetic risk factors are associated with genes known to be involved in the pathogenesis of NBD, together these genes only explain a fraction of the occurrence of the disease. Thus, there is a need to find the remaining genes that harbor causative or risk mutations/variations for one or more of these NBDs. Not only may these help in diagnosis, but such genes may identify new molecular pathways offering therapeutic opportunities for one or different NBD diseases simultaneously.

Summary

[6]Through family-based genetic studies we have associated the gene DPP6 to NBD. Using gene-based and whole-genome sequencing, we have found that highly penetrant deleterious mutations affecting DPP6 are causative of different NBDs.

[7]Additionally, we have identified in NBD patient cohorts genetic variations in DPP6 that are genetically associated with increased risk for NBDs.

[8]Accordingly, it is an object of the invention to provide methods of diagnosing a neurodegenerative brain disease (NBD) in a subject, comprising determining the presence of one or more mutations in the DPP6 gene and/or determining the functional expression levels of DPP6 in a sample of said subject. Indeed, a decrease in functional levels of DPP6 (through any mechanism: e.g. by sole presence of mutated DPP6, or by decreased levels of wild type DPP6) will affect the risk of developing a neurodegenerative brain disease (particularly in case of a relatively small decrease) or even be causative of a neurodegenerative brain disease (particularly in cases where functional DPP6 levels are significantly affected).

[9] Particularly, the NBD is selected from the group of Alzheimer disease (AD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and FTLD/ALS. More particularly, the neurodegenerative brain disease is a neurodegenerative dementia. Most particularly, the NBD is selected from the group of AD and FTLD.

[10]In case expression levels of DPP6 are monitored, altered expression is indicative of the presence of a NBD. Expression levels can be assessed using methods well known in the art. Without being limited to a particular technology, this can be using quantitative RT-PCR (e.g. for determining mRNA levels of DPP6) or using ELISA or Western Blot (e.g. for determining protein levels of DPP6). Additionally or alternatively, the presence of one or more mutations in the DPP6 gene may be determined. Most particularly, the mutations will have a deleterious effect on DPP6 gene function, either by altering (e.g. decreasing) expression levels of the gene, or by decreasing or altering its function.

[11]It is particularly envisaged that the one or more mutations are selected from mutations affecting the coding regions of DPP6, particularly exonic mutations, and complex genomic mutations affecting gene expression of DPP6. Mutations affecting the coding regions of DPP6 typically are selected from missense mutations, nonsense mutations and frame-shift mutations. Genomic mutations affecting gene expression are typically selected from inversions, deletions or duplications (the latter two can be

indicated as CNVs). According to particular embodiments, mutations affecting translation into DPP6 protein or transcript stability that are not in the coding regions of DPP6 are also envisaged. Typically, these are mutations in the translation initiation codon or in regulatory sequences such as those regulating splicing, transcript stability or turn-over. According to these embodiments, the DPP6 mutations are selected from mutations affecting transcript stability, translation or protein function and/or conformation.

[12]According to particular embodiments, at least one of the mutations of which the presence is determined is a mutation in the extracellular domain of DPP6.

[13]According to particular embodiments, at least one of the mutations is selected from those listed in Table 6 (particularly 6A and 6C, more particularly 6A), Table 8, and an inversion or CNV affecting DPP6. More particularly, it is envisaged that at least one of the mutations whose presence is determined is a mutation selected from those listed in Table 6 and in Table 8, and an inversion affecting DPP6. More particularly, it is envisaged that at least one of the mutations whose presence is determined is a mutation selected from those listed in Table 6 and in Table 8. According to even further embodiments, at least one of the mutations is selected from the mutations listed in Table 6.

[14]According to particular embodiments, when diagnosis is based on mutations, at least one mutation is a null mutation and is causative of the neurodegenerative brain disease (i.e., is a high penetrant causal mutation). According to alternative, but compatible embodiments, when diagnosis is based on expression levels, the functional expression levels of DPP6 are decreased by at least 20%, and this is causative of the neurodegenerative brain disease. According to further specific embodiments, the decrease in expression levels is at least 30% or at least 40%.

[15]According to alternative embodiments, when diagnosis is based on mutations, the one or more mutations are not null mutations and are indicative of an increased risk of developing or presence of the neurodegenerative brain disease. I.e., they are mutations with incomplete penetrance. According to alternative, but compatible embodiments, when diagnosis is based on expression levels, the functional expression levels of DPP6 are decreased by less than 20%, and this is indicative of an increased risk of developing or presence of the neurodegenerative brain disease. According to alternative embodiments, a decrease of less than 30%, or less than 40% is indicative of an increased risk of developing or presence of the neurodegenerative brain disease. The methods can be performed using direct sequencing methods or others. According to particular embodiments, detection of mutations is done using (e.g. DNA and/or cDNA) sequencing, a hybridization assay or PC -based assay, a cytogenetic method, or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

According to particular embodiments the sample in which mutations in DPP6 are determined is selected from blood, fibroblasts or tissue. According to further embodiments the sample in which expression of DPP6 is determined is selected from tissue, fibroblasts, iPS cells, neuronal cells or cell lines. According to a further aspect, kits are provided comprising at least one primer or probe suitable to determine the presence of one or more mutations in DPP6. According to alternative/additional embodiments, kits are provided comprising suitable means for determining the expression levels of DPP6, e.g. T-qPC primers and Taqman probes.

[16]In yet another aspect, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided for use as a medicament. Most particularly, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided for use as a diagnostic.

[17]According to specific embodiments, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided for use in treating NBD as described herein. Treating can also mean delay the onset of, or prevent the onset of, the NBD. Most particularly, the NBD is selected from AD and FTLD. This is equivalent as saying that methods of treating NBD (particularly AD or FTLD) in a subject in need thereof are provided, comprising restoring the levels of DPP6 in said subject (e.g. increasing DPP6 levels in case of a loss-of-function). It is specifically envisaged that the levels of DPP6 are increased by administering the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, to said subject. This can for instance be achieved using a gene therapy method. However, it is also envisaged that levels of DPP6 can also be restored to normal levels by administering a compound that restores DPP6 expression. For instance, in case of reduced DPP6 levels, the levels can be increased. In case of excessive DPP6 expression (e.g. because of a gain-of-function), the levels can be decreased.

[18]Accordingly, in a further aspect, methods to screen for compounds that restore DPP6 expression are provided, comprising:

[19]Providing a sample of cells with decreased functional expression of DPP6; or providing a sample of cells expressing a mutant form of DPP6;

[20] Adding a compound to said cells;

[21] Evaluating the expression of DPP6 after addition of the compound.

Brief description of the Figures

[22]Figure 1 shows the pedigree of family 1270. A black filled symbol characterizes a patient and a white unfilled symbol an unaffected individual or an at-risk individual with unknown phenotype. The Roman numbers on the left of the pedigree denote generations. Arabic numbers above the symbols denote individuals. The Arabic numbers below the symbols denote age-at-onset for patients or either age at last examination or age at death for unaffected individuals and at-risk individuals with unknown phenotype. An asterisk (*) indicates an individual who was included in the linkage analysis. The arrow identifies the proband with early age at onset AD (47 years). Patients used in WGS are circled.

[23]Figure 2: Disguised linkage pedigree of family 1270 (fig. 1). Haplotypes are based on 17 informative polymorphic genetic microsatellite markers at chromosome band 7q36. Haplotypes for individuals from the first and second generations were inferred from genotype data of siblings and offspring. The risk haplotype was arbitrarily set for individual 1-2. For confidentiality reasons, haplotypes are shown only for patients; the number of at-risk individuals included in the genotyping is indicated by numbers within diamonds.

[24]Figure 3: Linkage pedigrees of Dutch families with early-onset AD who share haplotypes at 7q36. A black filled symbol represents a patient and a white symbol represents an unaffected individual or an at-risk individual with unknown phenotype. The Roman numbers on the left of the pedigree denote generations; Arabic numbers above the symbols denote individuals. For patients, the age (in years) at onset is shown below the symbol. An asterisk (*) indicates that DNA was available for genetic analysis. The arrow identifies the proband. Haplotypes for individuals 111-20 in family 1242 and individual 111-4 in family 1034 were reconstructed from genotype data obtained from their siblings and offspring. For family 1125, only genotype data are given, since segregation data were not informative for deduction of haplotype.

[25]Figure 4: Schematic presentation of alternate transcriptional splice variants of DPP6. DPP6 has 3 transcripts resulting in 3 different isoforms. Both isoforms 2 and 3 have a distinct N-terminus, compared to isoform 1. Note: The gene spans an assembly gap in intron 5 of 100 kb.

[26]Figure 5: Schematic presentation of the location of the inversion breakpoint relatively to DPP6 isoforms and promoters. The blue bar denotes part of the linked region of family 1270, the dark blue bar part of the shared haplotype between the 4 families and the green bar part of the inversion. The 3 DPP6

isoforms have each a different core promoter predicted by FirstEF (First-Exon and Promoter Prediction) based on high GC content, and a distinct translation initiation codon within their own exon 1.

[27]Figure 6: Graphical presentation of the haplotype sharing between families 1270, 1034, 1125 and 1242. The differently colored horizontal bars represent (part of) he shared haplotype region in each family based on allele sharing (Table 2). The red horizontal bar is the minimal shared haplotype derived for allele and haplotype sharing in all 4 families (Figure 3).

[28]Figure 7: Structure of DPP6 (Strop et al., 2004). (a) Ribbon diagram of DPP6 dimer. The color changes from blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus). Carbohydrates with glycosylation sites are shown in ball- and-stick representation and the "catalytic triad" is shown in CPK representation. (b)View of the eight- bladed β-propeller domain (residues 142-322 and 352-581) c) View of the α/β hydrolase domain (residues 127-142 and 581-849). The color scheme is the same as used in a). Figure 8: Schematic presentation of DPP6 isoforms and location of the rare non-synonymous variants. Shown are rare non-synonymous variations identified only in patients (above horizontal bar) or only in controls (below horizontal bar). Rare mutations identified in both controls and patients have not been included in the figure. The position of the structural domains is as reported in Strop et al., 2004 (Figure 7).

[29]Figure 9: protein structure details of DPP6 showing how mutation may affect interaction with functional residues. A, interaction of p.322 (wt) with p.N319; B, interaction of p.D659 (wt) with p.N566.

[30]Figure 10: Scatter plot of pooled relative expression levels of DPP6 in patients vs control individuals.

[31]Figure 11: Relative expression levels of total DPP6. The two blue bars on the left represent the average levels in controls vs DPP6 carriers. The middle three red bars are the expression levels in the separate carrier individuals, the green bar on the right represents the expression levels in the VCP mutation carrier only. Panel A and B reports the relative expression levels obtain from two independent experiments.

[32]Figure 12: DPP6 antibody optimization. Two concentrations tested (1/500 and 1/1000). Right panel shows reactivity of the antibody vs human and mouse DPP6.

Figure 13: Western Blot of patient and control DPP6 levels. Normalization vs beta-actin (lower pa confirms lowered expression in patients.

[35] The present invention will be described with respect to particular embodiments and with reference to certain drawings but the invention is not limited thereto but only by the claims. Any reference signs in the claims shall not be construed as limiting the scope. The drawings described are only schematic and are non-limiting. In the drawings, the size of some of the elements may be exaggerated and not drawn on scale for illustrative purposes. Where the term "comprising" is used in the present description and claims, it does not exclude other elements or steps. Where an indefinite or definite article is used when referring to a singular noun e.g. "a" or "an", "the", this includes a plural of that noun unless something else is specifically stated. Furthermore, the terms first, second, third and the like in the description and in the claims, are used for distinguishing between similar elements and not necessarily for describing a sequential or chronological order. It is to be understood that the terms so used are interchangeable under appropriate circumstances and that the embodiments of the invention described herein are capable of operation in other sequences than described or illustrated herein. The following terms or definitions are provided solely to aid in the understanding of the invention. Unless specifically defined herein, all terms used herein have the same meaning as they would to one skilled in the art of the present invention. Practitioners are particularly directed to Sambrook et al., Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed., Cold Spring Harbor Press, Plainsview, New York (1989); and Ausubel et al., Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Supplement 47), John Wiley & Sons, New York (1999), for definitions and terms of the art. The definitions provided herein should not be construed to have a scope less than understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art.

[36]The term "neurodegenerative brain disease (NBD)" as used herein refers to a group of degenerative disorders characterized by a progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, including death of neurons. Most particularly, it refers to a group including Alzheimer's disease (classified under G30 in ICD-10), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) or frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (used as synonyms herein, classified under G31 in ICD-10), Pick disease (G31.0), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (G31.8), Parkinson's disease (PD) (G20-22), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (G12.2), and/or diseases of the FTLD/ALS spectrum.

The term "DPP6" as used herein refers to the dipeptidyl-peptidase 6 gene (Gene ID: 1804 in humans), and its encoded protein, as well as the m NA that is transcribed from the gene. The DPP6 gene encodes a single-pass type II membrane protein that is a member of the S9B family in clan SC of the serine proteases. This protein has no detectable protease activity, most likely due to the absence of the conserved serine residue normally present in the catalytic domain of serine proteases. However, it does bind specific voltage-gated potassium channels and alters their expression and biophysical properties. Alternate transcriptional splice variants, encoding (at least) three different isoforms, have been characterized. Unless specifically mentioned otherwise, the term DPP6 encompasses the different isoforms. The phrase "mutation in the DPP6 gene" or "mutation in DPP6" as used herein refers to mutations in the coding sequence of the gene as well as mutations in the non-coding regions (e.g. introns, promoter region, UTR). Examples of mutations include, but are not limited to, substitutions, insertions, deletions, indels, amplifications, inversions, copy-number-variations (CNV). Mutations can have different effects, e.g. loss-of-function (up to complete loss-of-function, i.e. amorphic mutations), gain-of-function, dominant negative mutation, and so on. Importantly, mutations resulting in decreased transcription or translation are also regarded as loss-of-function mutations. Note that mutations as used herein covers both mutations that are causative of the disease (high penetrant, pathogenic mutations) as those that only confer an increased risk of developing the disease (i.e. low to median penetrant mutations). According to particularly envisaged embodiments, the mutations are null mutations.

[37] Although not limited thereto, like for other genes, a mutation in the DPP6 gene will typically be a small scale mutation, i.e. only comprise one or a few nucleotides (note that, in case of frameshift or nonsense mutations, a change of even one nucleotide in the genomic sequence may lead to a much larger difference in the resulting gene product). Larger mutations are envisaged as well within the definition. A particular class of mutations are complex genomic mutations. The term "complex genomic mutation" or "genomic mutation" is used herein to indicate structural variations that affect more than one gene (as opposed to single nucleotide changes, which are limited to one gene). These genomic mutations may also be indicated as large-scale mutations in chromosomal structure, and typically affect at least one kilobase (1000 nucleotides) but may be much larger (up to several megabases). Typical examples include, but are not limited to: amplifications (or gene duplications) leading to more than one copy of a chromosomal region, deletions of large chromosomal regions (leading to loss of the genes within those regions), chromosomal translocations (interchange of genetic parts from nonhomologous chromosomes), interstitial deletions (an intra-chromosomal deletion that removes a segment of DNA from a single chromosome), chromosomal inversions (reversing the orientation of a

chromosomal segment). Copy-number variations (CNVs) is the term used to indicate the group of structural variations formed by amplifications and deletions.

[38] When a complex genomic mutation affects part of the (coding or non-coding) sequence of the DPP6 gene, it is envisaged within the definition of "mutation in DPP6". However, DPP6 is located in a low copy repeat (LC ) region in the human genome, and it is known that such regions, due to their high sequence identity as a result of segmental duplication, are prone to non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR), leading to genomic mutations (deletions, duplications and inversions). It is envisaged that mutations in the DPP6 genomic region may arise that do not affect the DPP6 gene sequence, but cause instability of DPP6 (e.g. because transcription of DPP6 is affected). Although such mutations are not a mutation in DPP6, they do affect functional expression of DPP6 and are envisaged under that terminology.

[39] With "functional expression" of DPP6, it is meant the transcription and/or translation of functional gene product. "Functional expression" can be deregulated on at least three levels. First, at the DNA level, e.g. by absence or disruption of the gene, or lack of transcription taking place (in both instances preventing synthesis of the relevant gene product). The lack of transcription can e.g. be caused by epigenetic changes (e.g. DNA methylation) or by loss of function mutations. A "loss-of-function" or "LOF" mutation as used herein is a mutation that prevents, reduces or abolishes the function of a gene product as opposed to a gain-of-function mutation that confers enhanced or new activity on a protein. LOF can be caused by a wide range of mutation types, including, but not limited to, a deletion of the entire gene or part of the gene, splice site mutations, frame-shift mutations caused by small insertions and deletions, nonsense mutations, missense mutations replacing an essential amino acid and mutations preventing correct cellular localization of the product. Also included within this definition are mutations in promoters or regulatory regions of the DPP6 gene if these interfere with gene function. A null mutation is an LOF mutation that completely abolishes the function of the gene product. A null mutation in one allele will typically reduce expression levels by 50%, but may have severe effects on the function of the gene product. Note that functional expression can also be deregulated because of a gain of function mutation: by conferring a new activity on the protein, the normal function of the protein is deregulated, and less functionally active protein is expressed.

[40]Second, at the RNA level, e.g. by lack of efficient translation taking place - e.g. because of destabilization of the mRNA (e.g. by UTR variants) so that it is degraded before translation occurs from the transcript. Or by lack of efficient transcription, e.g. because a mutation introduces a new splicing variant.

[41] Third, at the protein level, e.g. because of protein instability, proteins with reduced functionality or activity (e.g. enzymatic activity, or binding activity, such as the binding to voltage-gated potassium

channels), truncated proteins, and/or proteins with altered function (e.g. as a result of a gain of function mutation). For instance, while a truncated protein may be equally expressed as the wild type counterpart, this will typically result in a decrease in functional expression (or functional expression levels), since the truncated protein will be less active (or less functional).

[42]Notably, another way in which functional DPP6 may be decreased, is by affecting post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation. Indeed, it is known that correct glycosylation is important for protein function, and we have identified several mutations in NBD patients that affect glycosylation. Thus, mutations affecting glycosylation of DPP6 and thereby its function are also envisaged as mutations affecting functional levels of DPP6. Again, the essence is that a decrease in DPP6 functionality and/or its levels will increase risk of, or even cause, a neurodegenerative brain disease.

[43]The present application is the first to show that mutations in DPP6 (which have an effect on function or expression) or affecting DPP6 expression are found in patients with different NBD, most particularly AD and FTLD (including FTLD/ALS), and are causative of the disease, or predispose to an increased risk of having or developing the NBD. Accordingly, in a first aspect, methods are provided of diagnosing the presence of and/or risk of developing a NBD in a subject, comprising determining the presence of one or more mutations in the DPP6 gene and/or determining the functional expression levels of DPP6 in a sample of said subject.

[44]According to particularly envisaged embodiments, the NBD is Alzheimer disease, FTLD, FTLD/ALS, or ALS. Although mutations in DPP6 were primarily identified in AD or FTLD, it is well established that carriers of such mutations are often also at a higher risk of other NBD, cf. e.g. the progranulin missense mutations found in AD. Further characterization of the DPP6 gene is ongoing in patients with ALS, dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease and others. According to particular embodiments, the neurodegenerative brain disease does not encompass multiple sclerosis (MS).

[45]In those embodiments where the presence of one or more mutations (or genetic variations) is determined, the one or more mutations whose presence is determined are typically mutations affecting the function of DPP6, or the amount of functional DPP6 protein. Most typically, the mutations will decrease the function of DPP6 or the amount of functional DPP6 protein. Note that mutations affecting DNA or NA are included within the mutations that affect function or amount of protein: absence of protein is also a decrease in function or amount. Thus, in these embodiments, the one or more mutations will be deleterious mutations, or even null mutations or loss-of-function mutations. The presence of these deleterious mutations is indicative of an increased risk of developing, or of the

presence of neurodegenerative disease (depending i.a. of the age of the subject when the presence of mutations is determined).

[46]The effect of DPP6 mutations or expression levels on NBD is already noticeable in the heterozygous state, and is dosage sensitive. In other words, any decrease in the amount of functional DPP6 will have an effect: the mutation does not need to lead to a complete loss of function. However, the dosage sensitivity implies that the more severe the effect of the mutation on the gene product, the stronger the effect on neurodegenerative brain disease. By way of non-limiting example, a mutation that decreases expression of functional DPP6 protein by 10% will likely confer just an increased risk to develop neurodegenerative disease, while a null mutation (or null allele) decreasing functional protein by 50% or more is likely high-penetrant and can cause early-onset neurodegenerative disease.

[47]"Penetrance" of DPP6 mutations as used herein refers to the proportion of individuals carrying a particular variant of DPP6 (allele or genotype) that also exhibits (or will develop) clinical symptoms of a NBD. For example, if a mutation in DPP6 has 95% penetrance, then 95% of those with the mutation will develop a neurodegenerative brain disease, while 5% will not. The frequencies indicated to characterize penetrance are typically age-related cumulative frequencies: while an individual carrying a highly penetrant mutation will normally develop disease, it is very well possible that the individual does not have the disease yet at time of diagnosis. For instance, considering that NBDs most often affect middle-aged to older subjects, if the diagnosis is done on a pre-adolescent, an adolescent or a young adult individual, the diagnosis is more likely to relate to the increased risk of developing disease than on presence of disease. "High penetrance" or "high-penetrant mutations" as used herein refers to mutations with an age-related cumulative frequency of at least 80%. "Median penetrance" or "incomplete penetrance" as used herein refers to mutations with an age-related cumulative frequency of between 20 and 80%, or particularly between 30 and 80% or between 40 and 80%.

[48]According to very specific embodiments, particularly when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutations whose presence is determined do not encompass rsl0260404. Of note, this SNP in the DPP6 genomic region has been identified in a GWAS study as being associated with susceptibility to ALS (Van Es et al., 2008). The difference between the present findings and GWAS is that genome-wide association studies identify SNPs and other variants in DNA which are associated with a disease, but cannot on their own specify which genes are causal. The SNP identified in an intronic region has no effect on protein function and expression. This is distinct from the present invention, where it could be shown that altered levels or function of DPP6 (e.g. because of an inversion) are indeed causative of neurodegenerative disease. The SNP identified is not a deleterious mutation affecting DPP6.

According to other very specific embodiments, particularly when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutations whose presence is determined are not CNVs. According to yet other very specific embodiments, particularly when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutation whose presence is determined are not in intron 3. According to yet other very specific embodiments, particularly when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutation whose presence is determined is not in the 5' region of DPP6. According to even further specific embodiments, particularly when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutation whose presence is determined does not encompass a CNV in intron 3. According to even further specific embodiments, particularly when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutation whose presence is determined does not encompass a CNV in the 5' region of DPP6. According to yet other very specific embodiments, when the neurodegenerative disease is ALS, the one or more mutations whose presence is determined are exonic mutations. According to yet even other very specific embodiments, the neurodegenerative disease that is diagnosed is not ALS, with the exception of FTLD/ALS cases. According to yet even other very specific embodiments, the neurodegenerative disease that is diagnosed is not ALS.

[49]A subject typically is a vertebrate subject, more typically a mammalian subject, most typically a human subject. A sample of the subject will typically contain cells (or at least cellular material) of the subject, to evaluate the expression or presence of mutations in the genetic material. A sample can be obtained from any tissue to establish the presence of germline mutations, and can be a tissue sample, or a fluid sample (e.g. blood, saliva). Particularly when expression of the DPP6 gene is assessed, it is envisaged to use a sample from a tissue which can be linked to the presence of neurodegenerative disease, such as a brain sample or a CSF sample. Other samples that are particularly envisaged include neuronal cells, neuronal cell lines (particularly primary cell cultures, most particularly primary cell cultures derived from the subject to be diagnosed), iPS cells and fibroblasts. The samples can be used as such or can be pre-processed (e.g. lysed) using methods routinely used in the art.

[50]When the methods of diagnosing a neurodegenerative disease involve detection of functional expression of DPP6, typically, these methods will further include a step involving correlating the levels of DPP6 gene product to the risk of presence or development of neurodegenerative brain disease, particularly correlating decreased levels (or even absence) of DPP6 gene product to increased risk of neurodegenerative disease. However, the reverse can also be true: concluding from an observation that the DPP6 gene product levels are not decreased, or are even increased, in the sample, that there is no increased risk of neurodegenerative disease, or in some instances even a decreased risk of neurodegenerative disease.

Decreased levels of DPP6 gene product are typically decreased versus a control. The skilled person is capable of picking the most relevant control. This will typically also depend on the nature of the disease studied, the sample(s) that is/are available, and so on. Suitable controls include, but are not limited to, similar samples from subjects not having neurodegenerative disease, the average levels in a control group, or a set of clinical data on average DPP6 gene product levels in the tissue from which the sample is taken. As is evident from the foregoing, the control may be from the same subject, or from one or more different subjects or derived from clinical data. Optionally, the control is matched for e.g. sex, age etc.

[51]With 'decreased' levels of DPP6 gene product as mentioned herein, it is meant levels that are lower than are normally present. Typically, this can be assessed by comparing to control. According to particular embodiments, decreased levels of DPP6 are levels that are 10%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 75%, 80%, 90%, 100%, 150%, 200% or even more low than those of the control. According to further particular embodiments, it means that DPP6 gene product is absent, whereas it normally (or in control) is expressed or present. In other words, in these embodiments determining the presence of DPP6 gene product is equivalent to detecting the absence of DPP6 gene product. Typically, in such cases, a control will be included to make sure the detection reaction worked properly. The skilled person will appreciate that the exact levels by which DPP6 gene product needs to be lower in order to allow a reliable and reproducible diagnosis may depend on the type of sample tested and of which product (mRNA, protein) the levels are assessed. However, assessing the correlation itself is fairly straightforward.

[52]Instead of looking at decreased levels compared to a healthy control, the skilled person will appreciate that the reverse, comparing to a control with disease, can also be done. Thus, if the DPP6 gene product levels measured in the sample are similar to those of a sample with neurodegenerative disease, (or are e.g. comparable to DPP6 gene product levels found in a clinical data set of neurodegenerative disease), this may be considered equivalent to decreased DPP6 gene product levels compared to a healthy control, and be correlated to an increased risk of neurodegenerative disease. In the other case, if DPP6 gene product levels are higher than those of a control with neurodegenerative disease, this can be said not to correlate with an increased risk of neurodegenerative disease, or even to be correlated with a decreased risk of disease. Of course, DPP6 gene product levels may be compared to both a negative and a positive control in order to increase accuracy of the diagnosis.

[53]The DPP6 gene product whose levels are determined will typically be DPP6 mRNA and/or DPP6 protein. When DPP6 mRNA is chosen as the (or one of the) DPP6 gene product whose levels are determined, this can be the total of all DPP6 mRNA isoforms, or one or more specific mRNAs (e.g. isoform 1 of

DPP6). Alternatively or additionally, the DPP6 gene product of which the levels are determined may be DPP6 protein. As protein is translated from m NA and the mRNA exists in multiple isoforms, the same considerations apply: the total DPP6 levels may be determined, or those of specific isoforms only (e.g. using an antibody against the different N-termini). Most particularly, all DPP6 protein isoforms may be detected (e.g. using an antibody against a common epitope). Of note, it is envisaged as well that both DPP6 mRNA and DPP6 protein are determined. In this case, the isoforms to be detected can be all isoforms for both mRNA and protein, identical isoforms (wholly overlapping), or different isoforms (partly or not overlapping), depending on the setup of the experiment. With identical isoforms, it is meant that the mRNA isoform encodes for the corresponding protein isoform. According to particular embodiments, when diagnosis is based on mutations, at least one mutation is a null mutation and is causative of the neurodegenerative brain disease. According to alternative, but compatible embodiments, when diagnosis is based on expression levels, the functional expression levels of DPP6 are decreased by at least 20%, 30% or even 40%, and this is causative of the neurodegenerative brain disease. A 'null allele' or 'null mutation' as used herein is a mutant copy of a gene that completely lacks that gene's (i.e. typically DPP6) normal function. This can be the result of the complete absence of the gene at the genomic level, gene product (protein, RNA) at the molecular level, or the expression of a nonfunctional gene product. In the latter case, expression of gene product may be quite high, but this still corresponds to a significant decrease of functional expression, since no functional product is formed. A null allele may be a protein null or a RNA null (either at RNA or DNA level).

[54]According to particular embodiments, the neurodegenerative brain disease is early-onset brain disease. Early-onset brain disease is typically disease with an age at onset of 65 years or younger. According to particular embodiments, early-onset brain disease is brain disease with an age at onset (AAO) of 60 years or younger. As mentioned, the effect of the DPP6 gene is dosage sensitive, and the more severe the mutation (i.e., the more severe its effect on function of DPP6 or on functional levels of DPP6 gene product), the stronger the effect on disease. Thus, it is particularly envisaged that patients with null alleles of DPP6, a complete loss of function of DPP6, or where both alleles carry a mutation in DPP6, or with functional expression levels that are 50% or less of controls will have an earlier age at onset than carriers of less severe mutations. According to alternative embodiments, when diagnosis is based on mutations, the one or more mutations are not null mutations and are indicative of an increased risk of developing or presence of the neurodegenerative brain disease. I.e., they are mutations with incomplete penetrance. According

to alternative, but compatible embodiments, when diagnosis is based on expression levels, the functional expression levels of DPP6 are decreased by less than 20%, 30% or even 40%, and this is indicative of an increased risk of developing or presence of the neurodegenerative brain disease.

[55]According to particular embodiments, the neurodegenerative brain disease is late-onset brain disease. This typically will be the case when monitoring DPP6 risk alleles, or when functional expression levels of DPP6 are still relatively high (e.g. 90% of control, 80% of control, 75% of control, 70% of control, 60% of control) as compared to null alleles. Risk alleles are alleles that themselves are not causative of the disease, but confer an increased risk of developing the disease, e.g. because they produce less functional gene product. The risk of presence or of developing a neurodegenerative disease is even larger if a mutation is present in more than one allele of DPP6, or if there is also a mutation present in another neurodegenerative brain disease-linked gene. Thus, the methods may further comprise determining the presence of mutations in other genes.

[56]As will be shown in the Examples section, there are different mutations in DPP6 that are deleterious. Typical examples of deleterious mutations include mutations that affect the coding regions of DPP6, particularly exonic mutations and splice site mutations. Most particularly, such exonic mutations are missense mutations, nonsense mutations and frame-shift mutations. For example, the extracellular domain of DPP6 is highly structured, and non-synonymous mutations in this domain have a high chance of affecting DPP6 function, by changing the DPP6 conformational structure. Accordingly, such mutations are explicitly envisaged. Alternative deleterious mutations are mutations affecting functional expression levels of DPP6, e.g. mutations in the promoter region, in enhancer regions, UTR variants and splicing variants. The chromosomal region where DPP6 is located is quite sensitive to genomic rearrangements due to the presence of low-copy-repeat sequences. Particularly envisaged deleterious mutations affecting DPP6 gene expression thus include genomic mutations, such as inversions, deletions and duplications. The latter two include copy number variants (CNVs). According to particular embodiments, the copy number variants that are evaluated do not include the CNVs described by Blauw et al. (Blauw et al., 2010). Although inversions and duplications adjacent to, but not including, the DPP6 gene may also have effects on expression levels, it is particularly envisaged that the inversions and/or duplications involve the DPP6 genomic region. According to particular embodiments, they involve the region of isoform 1 of DPP6. According to most particular embodiments, they involve the 5' region of isoform 1 of DPP6.

[57]In the Examples section, different deleterious mutations of DPP6 are listed that are found in patients with neurodegenerative disease. It is particularly envisaged that at least one of the mutations whose

presence is determined is a mutation selected from those listed in Table 6, Table 8, and an inversion or CNV affecting DPP6. More particularly, it is envisaged that at least one of the mutations whose presence is determined is a mutation selected from those listed in Table 6 and in Table 8, and an inversion affecting DPP6. More particularly, it is envisaged that at least one of the mutations whose presence is determined is a mutation selected from those listed in Table 6 and in Table 8. According to even further embodiments, at least one of the mutations is selected from the mutations listed in Table 6.

[58]In order to accurately determine the risk of neurodegenerative disease, it is envisaged that the presence of more than one, and up to all, of these mutations are checked. For mutations affecting one or only a few amino acids, this can be done by sequencing of the entire DPP6 coding sequence and splice sites, or it can be done using multiple hybridization reactions or PCR reactions (the latter may also be multiplex PCR, wherein more than one mutation can be determined in the same assay). The nature of the assay is not vital to the invention, and the skilled person is capable of choosing the most appropriate assay. By way of non-limiting examples, according to particular embodiments, detection of mutations is done using sequencing, a hybridisation assay or PCR-based assay, such as the MastR™ assay (Multiplex Amplification of Specific Targets for Resequencing, Multiplicom). These assays can be used for sequencing or determining the presence of mutations in both exons and regulatory regions. Other methods include e.g. cDNA sequencing to detect e.g. exon(s) deletions other than caused by splice site mutations. For larger mutations, e.g. genomic rearrangements including inversions, deletions or duplications (CNVs), determining the presence will typically be done in other ways. For instance, cytogenetic methods may be used, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on stretched-chromosomes, which is suitable to detect inversions, deletions or duplications (as e.g. described by Salomon-Nguyen et al., 1998; Gijselinck et al., 2008). Alternatively, MAQ (Multiplex Amplicon Quantification) assays (Multiplicom) or pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (e.g. Davis, 1991) may be used. Here also, the skilled person is capable of selecting the most appropriate assay, and the listed methodologies should not be interpreted as limiting.

[59]According to a further aspect, kits are provided suitable for practicing the methods presented herein, i.e. kits for determining the expression levels of DPP6 and/or determining the presence of one or more mutations in the DPP6 gene in a sample of said subject. For determining expression, these kits will typically contain at least one agent specifically binding to DPP6 protein (e.g. a DPP6 antibody), or to DPP6 mRNA (e.g. primers). For determining the presence of one or more mutations, the kits will typically comprise at least one primer or probe suitable to determine the presence of one or more

mutations in the DPP6 gene. For larger mutations (e.g. genomic rearrangements like CNVs, inversions), the kits may provide the material to perform FISH, MAQ or PFGE, as described above. Obviously, kits may contain further material, such as pharmaceutically acceptable excipients or buffers, as is established in the art. According to a further aspect, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided for use as a medicament. According to one embodiment, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided as a diagnostic. Indeed, as described in the methods above, the levels and/or presence of mutations in DPP6 may be used as diagnostic tool to establish the presence of neurodegenerative disease. According to specific embodiments, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided as a diagnostic for diagnosing AD or FTLD (including FTLD/ALS).

[60]However, it is also envisaged that the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided for use as a medicament to treat neurodegenerative disease. Indeed, restoring correct levels of DPP6 levels will prevent the onset of, delay the onset of, or treat, neurodegenerative disease. Most particularly, the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, is provided for use in treating AD or FTLD (including FTLD/ALS).

[61]This is equivalent as stating that methods are provided of treating AD or FTLD in a subject in need thereof, comprising increasing the levels of DPP6 in said subject. According to particular embodiments, the levels of DPP6 are increased by administering the DPP6 protein, or nucleic acid encoding said protein, to said subject. According to yet further particular embodiments, the levels of DPP6 are increased using gene therapy, particularly gene therapy wherein the nucleic acid encoding said protein is administered to a subject in need thereof.

[62]Alternatively, DPP6 levels can also be increased by administering a compound to a subject. Without being bound to a particular mechanism, compounds can increase DPP6 expression e.g. by increasing DPP6 transcriptional activity, by stabilizing the DPP6 m NA or protein, or by influencing other genes or gene networks (e.g. by blocking DPP6 inhibitors).

[63]Accordingly, methods to screen for compounds that increase DPP6 expression are provided, comprising:

[64]Providing a sample of cells with decreased functional expression of DPP6; or providing a sample of cells which express a mutant form of DPP6;

[65] - Adding a compound to said cells;

[66] Evaluating the expression of DPP6 after addition of the compound.

It is to be understood that although particular embodiments, specific configurations as well as materials and/or molecules, have been discussed herein for cells and methods according to the present invention, various changes or modifications in form and detail may be made without departing from the scope and spirit of this invention. The following examples are provided to better illustrate particular embodiments, and they should not be considered limiting the application. The application is limited only by the claims.

[68]Example 1. Identification of DPP6 as the chromosome 7 gene for AD

[69]1.1 Existing knowledge on the chromosome 7 AD locus

[70]Multiplex family 1270 linked to chromosome 7q36

[71]Family 1270 was ascertained by her 47-year old proband who was included in the Rotterdam cohort (N = 198) of early-onset Alzheimer disease (AD) patients sampled in The Netherlands throughout the period 1980-1987 (Hofman et al., 1989). Patients were derived from a population-based epidemiological study of early-onset AD in four Northern provinces of The Netherlands and the area of metropolitan Rotterdam (Hofman et al., 1989). The study aimed at the complete ascertainment of all early-onset AD patients with a disease onset before the age of 65 years. The diagnosis of probable AD was independently confirmed by two neurologists using a standardized protocol according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for AD.

[72] Mutations in APP were excluded in 100 index patients (Rotterdam 100 cohort: average onset 57 years ± 5 years, including the proband of family 1270) of the Rotterdam early-onset AD cohort of whom DNA was available (van Duijn et al., 1991). In the overall Rotterdam cohort, strong association was obtained with APOE ε4, particularly in familial patients (van Duijn et al., 1994a). Of 10 familial probands from the Rotterdam cohort, the pedigree was consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance and informative for linkage studies, and relatives were sampled (van Duijn et al., 1994b). Linkage analysis with simple tandem repeat (STR) markers on chromosomes 14, 19 and 21 was performed but the data was mostly uninformative (van Duijn et al., 1994b). Mutation analysis of the presenilin genes, PSEN1 and PSEN2, was negative for family 1270 (Cruts et al., 1998). In addition mutations were excluded in exons 9-13 encoding the microtubule-binding domains of the microtubule associated protein tau gene (MAPT) (Roks et al., 1999). The initial Rotterdam early-onset Alzheimer study was extended between 1997 and

2000 in a genetically isolated part of the previously described area with the same sampling criteria (Dermaut et al., 2003). The current sample comprises 101 patients from the original group and 22 additional patients from the extended study. Median age at onset in this sample was 58.0 years (range 33-65) and 77% were women. In this extended sample, mutations were excluded in the prion gene (PRNP) (Dermaut et al., 2003). Conclusion, family 1270 was negative for the 3 causal AD genes APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2, plus for the PRNP and MAPT genes in which occasionally mutations have been observed in clinical diagnosed AD patients.

[73]A clinical follow-up of family 1270 was performed by neurological examination of incident patients, interviews of first-degree relatives and review of medical records (Rademakers et al., 2005). For five patients who were deceased or could not be examined, diagnosis was complemented by information obtained through a family informant. Since the first linkage report (van Duijn et al., 1994b), four family members (111-19, 111-21, 111-41, and 111-43) became symptomatic (Rademakers et al., 2005). The updated pedigree of family 1270 is shown in figure 1; clinical data is summarized in table l(Rademakers et al., 2005). At that time, the overall clinical picture of family 1270 was compatible with AD, with a mean (± SD) age at onset of 66.8±7.4 years (N=13; age range 47-77 years) and a mean duration of disease of 6.7±2.7 years (N=10; range of duration 4-13 years). In proband 111-45 and most other patients, the disease initially presented with memory impairment, except for patient 111-38, in whom a change of character was the initial complaint, later followed by memory loss. In all patients, the disease progressed into other areas of cognition, such as praxis and speech. Neuroimaging was available for two patients, 111-48 at age 74 years and 111-21 at age 82 years (table 1), which showed cortical atrophy in both patients. For the only living patient, 111-21, who received the diagnosis of possible AD, a recent CT scan at age 82 years showed that cortical and subcortical atrophy was most notable in the temporal and frontal regions. No brain pathology of deceased patients is available for family 1270.

[74]A genome-wide linkage analysis (GWL) using 400 STR markers generated a conclusive LOD score of 3.39 in the absence of recombinants (Θ = 0.00), with only one GWL STR marker, D7S798 at 7q36. All patients with AD and MCI were considered affected in the linkage analysis. The flanking markers, D7S636 and D7S2465, also showed positive LOD scores of 2.69 and 1.70, respectively, without recombinants. The finemapping of the linked region on chromosome 7 with additional STR markers identified a disease haplotype present in all patients. Obligate meiotic recombinants defined a candidate region of 19.7 cM between STR markers pRR8 and D7S559 with an estimated genomic size of 5.44 Mb (Rademakers et al., 2005).

Age (in years) at

[75] Patient Sex Disease Onset Death APOE Genotype3 Diagnosis

[76] 11-1 F 68 72 Dementia

[78] 11-6 M 63 74 Dementia13

[79] 11-7 F 65 70 Dementia13

[80] 111-12 M 77 >82 ε3ε3 Probable AD

[81] lll-19c M 75 80 ε3ε3 MCI

[82] lll-21c F 72 ε4ε4 Possible AD

[83] 111-36 M 65 70 Possible AD

[84] 111-38 M 64 72 ε3ε4 Probable AD

[85] lll-41c M 68 72 ε3ε3 Probable AD

[86] lll-43c F 65 71 Dementia13

[87] 111-45 F 47 60 ε4ε4 Probable AD

[88] 111-48 M 69 >75 ε3ε4 Probable AD

[89] Table 1: Clinical characteristics of patients of family 1270. Patient 111-45 is the index patient of Dutch family 1270 (Rademakers et al. 2005) and was part of the Rotterdam early-onset Alzheimer disease cohort (Hofman et al. 1989). a APOE genotypes of available patients in generation III (figure 1) b Diagnosis obtained through family informant c Newly diagnosed patients. Patients in red have been included in WGS.

[90]Allele sharing analysis in the Dutch population

[91] To estimate the contribution of the 7q36 locus in the Dutch population, we genotyped STR markers from the linked region in the AD patients (N = 102) from the population-based early-onset AD sample and age- and gender-matched control individuals (N = 187). Single-marker associations identified significant allelic association with D7S798 (P = 0.03) (table 3). This association could be explained in part by an increase of the rare 80-bp allele of marker D7S798, also linked to AD in family 1270, from 1.88% (7/372 alleles) in control individuals to 4.90% (10/204 alleles) in patients with early-onset AD (P = 0.04).

[92] Examination of individual genotype data of D7S798 revealed that 4 of the 10 patients with early-onset AD who carried the 80-bp allele at D7S798 were probands of families with autosomal dominant AD. We estimated that in the Dutch patient-control sample, the risk of AD for subjects carrying the 80-bp allele was 2.7 times higher (OR 2.69; 95% CI 1.01-7.17) than for non-carriers.

In the 3 Dutch families (1034, 1125 and 1242) in which the AD segregation pattern was consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance (figure 2) (van Duijn et al., 1994b), allele sharing with family 1270 was observed for all 3 families of the rare 80-bp allele (allele frequency 1.9%) at D7S798 and the flanking markers D7S2439 and D7S2546 (201-bp and 232-bp alleles) (Table 2). A frequency of 0.6% was calculated for the shared haplotype 201-80-232 on the basis of the frequencies of the 3 shared alleles in Dutch control individuals.

[93] Also, all 6 STR markers were genotyped in additional patients as well as relatives of families 1034 (2 patients), 1125 (2 patients) and 1242 (1 patient), and segregation analysis of the shared alleles was performed to define haplotypes (figure 3).

[95] allele linked allele in

[96] family control Genotype (allele in bp) of autosomal

[97] 1270 individuals dominant family

[98] Marker (bp) (%) 1034a 1125 1242c

[99] D7S642 189 45.4 189-191 195-195 191-191

[100] D7S2439 201 29.4 201-201 199-201 199-201

[101] D7S798 80 1.9 80-88 80-82 80 92

[102] D7S2546 232 18.6 232-236 232" 23 S 232-232

[103] D7S1823 217 12.3 221-225 221-229 209-237

[104] D7S2465 175 23.5 173-176 173-177 173-177

[105] Table 2: Allele-Sharing Analysis of Microsatellite Markers at 7q36. The linked alleles of family 1270 are in bold italics. In red the STR markers that showed allele sharing in all 4 families.

[106]In family 1034, all three patients with AD (111-4, 111-6, and 111-8) inherited the 201-80-232 haplotype. Segregation analysis of family 1242 revealed that both patients (111-14 and 111-20) carried the 80-232 haplotype. The lack of sufficient segregation information precluded haplotype determination in family 1125. However, allele sharing in the 2 additional patients from that family identified the linked 201-80- 232 alleles in 1 patient (lll-l), whereas the other patient (111-2) shared the 201-80 alleles. Together, these studies delineated a priority region— between markers D7S2439 and D7S2546, with a maximum genetic distance of 9.3 cM— that is shared by families 1270, 1034, 1242, and 1125.

[107] Sanger sequencing of the coding exons of the 29 known genes present in the candidate region, identified one linked silent mutation that affected PAX transactivation domain interacting protein gene

[108](PAXIP1, p.Ala626), but further experiments did not provide convincing evidence for a functional role of PAXIP1 in disease pathology (Rademakers et al., 2005). Additionally, array-based comparative

genomic hybridization (aCGH) for CNV analysis also failed to reveal evidence for disease-linked variations (unpublished data).

[109]1.2 Identification of DPP6 as the chromosome 7 gene for AD

[110]Whole genome sequencing in family 1270

[111] To elucidate the underlying genetic defect in family 1270, we outsourced whole genome sequencing (WGS) of 4 patients with probable AD from 3 different branches of the pedigree (Figure 1 and table 1, Patients 111-12, 111-38, 111-41 and 111-48) to Complete Genomics, Inc. In the sequence analyses, we focused on heterozygous variations shared by the 4 patients within the linked locus on chromosome 7, in search of noncoding variations able to explain the segregation with disease within the family.

[112] After the application of filtering steps based on quality and frequency data, a list of 79 variations was generated. Of these, 75 were true positive variants based on Sanger sequencing and Sequenom MassARRAY® data obtained for the 4 WGS patients. Of the 75 variants, 38 variants segregated on the disease haplotype in family 1270. Next, screening of a control group (n=800) evidenced that only 4 variations (arbitrary called vl, v2, v3 and v4) were unique for family 1270. The 3 variations vl, v2, and v3 were located within the intron 1 of the gene DPP6 (dipeptidyl peptidase 6), while v4 was mapped outside DPP6 at >lMb and several genes downstream of the DPP6 locus (data not shown). None of the 3 DPP6 intron 1 variations were present in a Belgian AD patient group (total screened n=1100). Furthermore, screening of the proband and relatives of the 3 Dutch families 1034, 1125 and 1242 (van Duijn et al., 1994b), who shared haplotypes at 7q36 (table 2, figure 2), showed that the 3 intron 1 variants were absent.

[113]Complexity of the genomic region surrounding DPP6 - detection of inversion

[114] We hypothesized that the disease segregation in family 1270 could be explained by the presence on the disease haplotype of a paracentric inversion with its distal inversion breakpoint located in intron 1 of DPP6.

[115] The hypothesis of an inversion arose from an empirical observation while designing primers for direct sequencing or high throughput genotyping Sequenom Mass Array® to genotype variations identified by WGS. We noticed that several primer pairs in silico amplified sequences on chromosome 7 at two different loci separated by approximately 3.6 Mb. We hypothesized that these sequences were located in paralogous sequences.

[116] A dotplot was made using the NCBI hgl9 reference sequence, for comparative sequence analysis of the genomic region of chromosome 7 ranging from 149169800 (where ZNF746 is located) to 154794690 (where PAXIP1 is located) (data not shown). The dotblot confirmed the presence of Low-Copy-Repeat

(LC s) in the 5' region of the DPP6 locus and provided evidence for the presence of inverted repeats in the LCRs (Table 8).

[117] Our data are supported by the data of a whole genome-wide search for inverted paralogous LCRs (IP- LCR) showing that the DPP6 locus is enriched for IP-LCRs (Dittwald et al., 2012). Inverted LCRs can mediate the formation of inversions by non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) (Feuk et al. 2006). Consequently, we hypothesized the presence of a genetically balanced inversion on the disease haplotype, with its distal inversion breakpoint in intron 1 of DPP6, explaining the empirical observation of the 2 amplification signals.

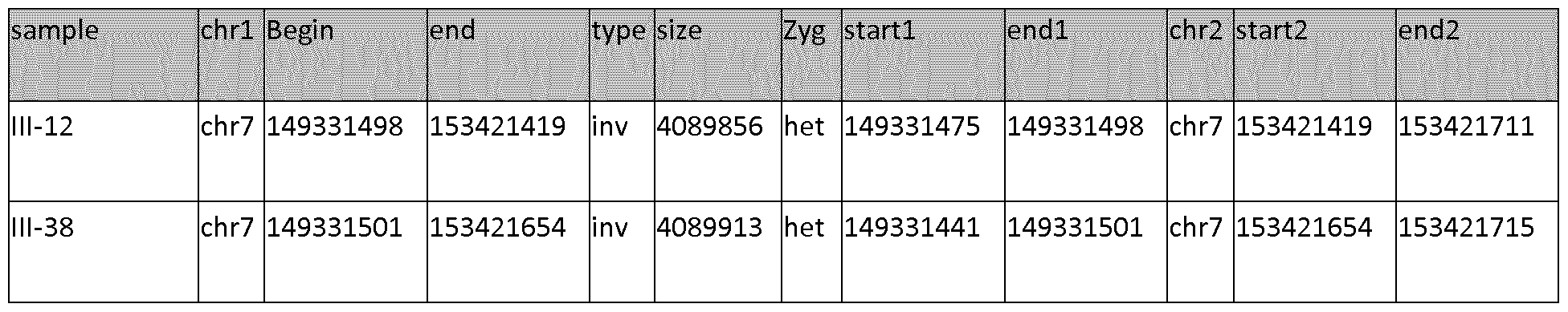

[118] Structural variations (SV) were called on the WGS data of the 4 sequenced members of family 1270. Investigation of the SV data for the DPP6 locus demonstrated the presence of a heterozygous inversion in two of the WGS patients (111-38 and 111-12, Pedigree figures 1 and 2). The inversion has an estimated size of ~4 Mb (Table 3) and the breakpoints are located in IP-LCRs. The 3 SNVs (vl, v2, v3) in intron 1 in family 1270 are located outside the inversion.

[119]

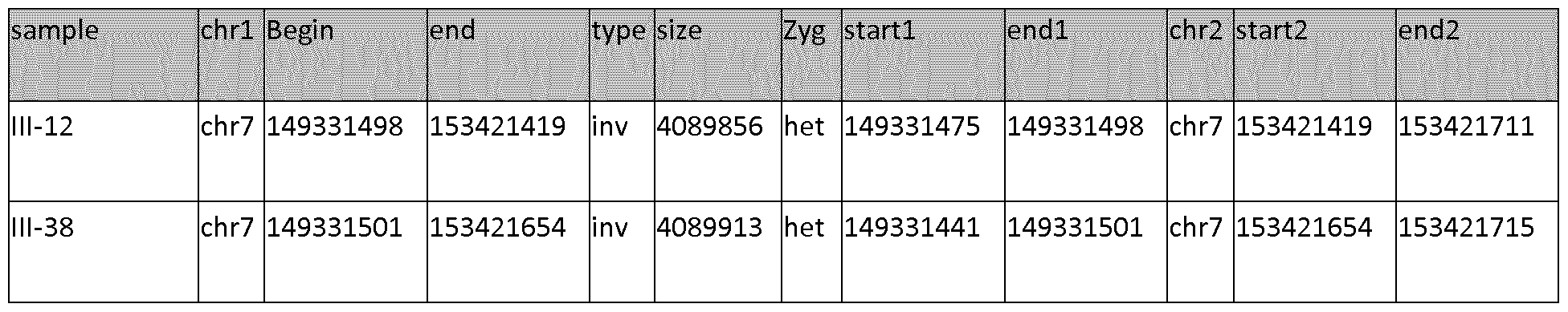

[120]Table 3: Summary of SV data, "chrl" and "chr2" refers to the chromosomal location of the breakpoints, "begin/end" indicates the genomic region on chromosome 7 involved in the inversion event. "Startl/endl" and "start2/end2" refer to the detected inversion breakpoints in the SV data.

[121]The 2 patients 111-12 and 111-38 with the called inversion belong to two different branches of the pedigree (Figure 2, descendants of patients 11-3 and of 11-6), suggesting that the inversion is located on the disease haplotype. Visual inspection of the raw mate pair data in the inversion region confirmed the presence of the inversion in the 2 other patients 111-41 (sib of 111-38, branch 11-6), and 111-48 (descendant of 11.7) (Table 4).

[122] Under normal conditions, the distance between the two ends of a mate pair is expected to be approximately 350 bp (distance inferred from documentation information available for the WGS). In the region of interest, however, the first end of the mate pair is located within the region spanning chr7:149331000-149332000 and the second end of the mate pair is located at a distance of ~4 Mb with opposite strand orientation, which is indicative of an inversion. A similar pattern of distribution was observed in all four affected relatives (not shown).

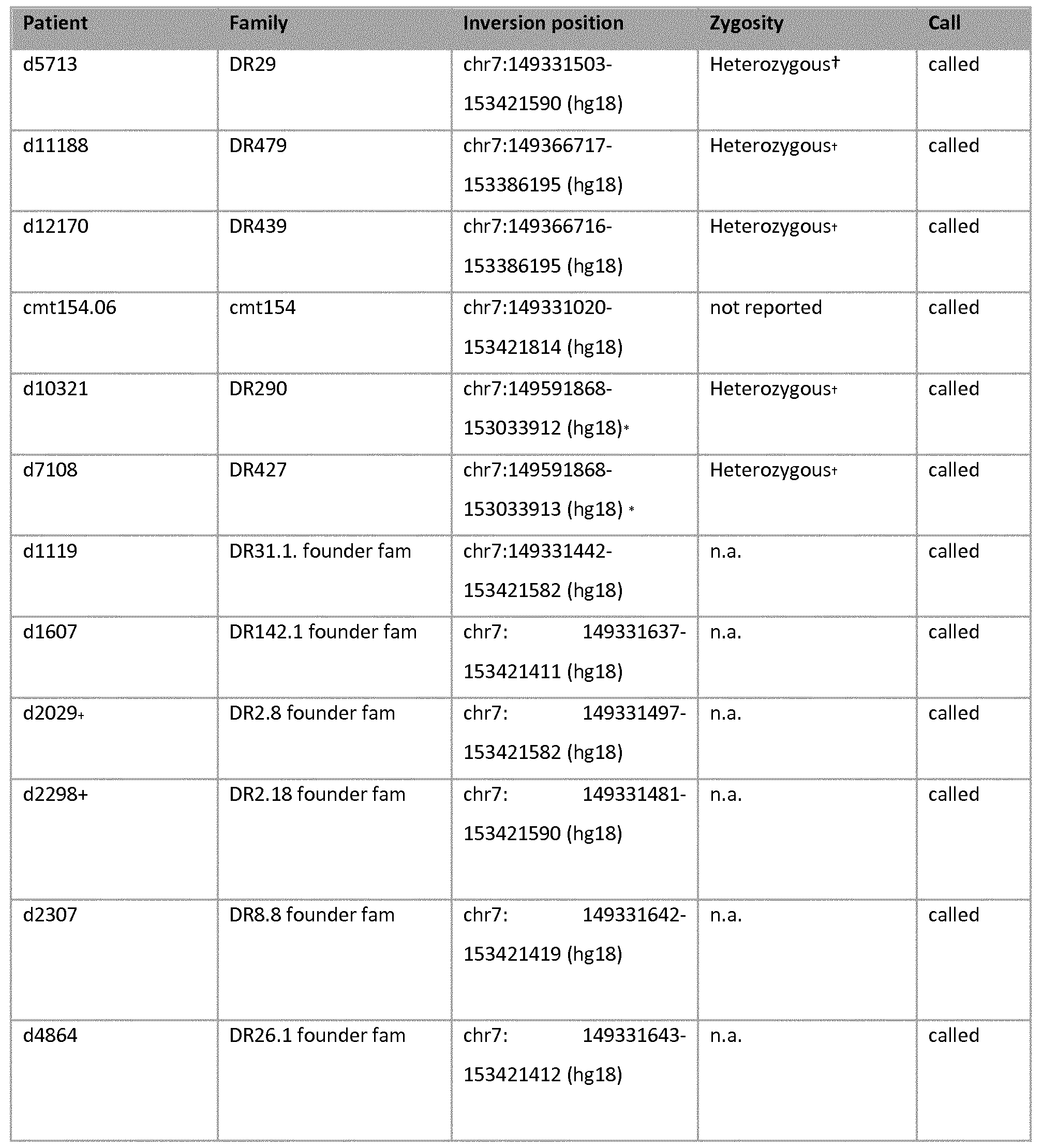

Patient Family Inversion position Zygosity Call d816 (111-38) 1270 chr7:149331501-153421654 (hgl8) Heterozygous called

[123] d820 (111-12) 1270 chr7:149331498-153421419 (hgl8) Heterozygous called

[124] d818 (111-41) 1270 same pattern n.a. extracted d820 (111-48) 1270 same pattern n.a. extracted dl0152 unknown chr7:149330954-153421889 (hgl8) not reported called

[125] Table 4: The inversions identified in WGS. The zygosity is mentioned only if reported in the SV data, "n.a."= "not available" because data have been extracted from the raw sequence reads. Further, we called for SV the WGS of 71 Belgian individuals of which 45 unrelated individuals, available in VIB DMG and obtained in different on-going NGS projects. The DPP6 inversion was observed in one Belgian patient, dl0152 (AD750.1; DEM6407), diagnosed with possible AD (onset age 64 years), a CSF biomarker profile indicative of early AD or MCI and a M I brain scan showing cortical and subcortical atrophy. Table 4 reports schematically the inversion information collected with the SV data analysis.

[126]Inversion breakpoint disrupting DPP6

[127] DPP6 has 3 major isoforms (Figure 4). DPP6 isoform 1 encodes the longest protein isoform (865 amino acids, also referred to as L). Isoform 2 and 3, include an alternate in-frame exon 1, compared to variant 1, resulting in shorter protein products that have a shorter and distinct N-terminus, compared to isoform 1 (isoform 2 has 803 amino acids while isoform 3 has 801 amino acids).

[128] The inversion breakpoint is positioned within intron 1 of isoforms 1 and 3 (Figure 5). The inversion is predicted to dislocate the exon 1 and promoter of these 2 isoforms and as such prevent their expression. It is also possible that the inversion breakpoint by its position affects the expression of isoform 2. We can also not exclude that the inversion affects an upstream enhancer regulating expression of some of all isoforms.

[129] The distal breakpoint of the inversion is part of the priority haplotype 201-80-232 delineated by the STR markers D7S2439 and D7S2546 shared between family 1270 and the 3 families 1034, 1125 and 1242 (Figure 6). DPP6 protein

[130] DPP6 is a single-pass type II transmembrane protein. It is a member of the S9B family that belongs to the group of serine proteases. Differently from the other family members, this protein has no detectable protease activity, due to the absence of the conserved serine residue normally present in the catalytic domain of serine proteases (NCBI, Gene database, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene).

The X-ray crystal structure of the extracellular domain of human DPP6 was determined at 3.0 A resolution (Strop et al., 2004). Two monomers associate to form a homodimer. Each monomer consists of eight-bladed β-propeller domain and a α/β hydrolase domain. Both the α/β hydrolase domain and the β-propeller domain participate in the formation of the dimer. The protein has seven predicted N- glycosylation sites and 4 disulfide bridges in each monomer (Figure 7) (Strop et al., 2004)

[131]The protein is expressed predominantly in brain, with high levels in amygdala, cingulate cortex, cerebellum and parietal lobe (http://biogps.org) where it can be expected to be involved in physiological processes of brain function. It modulates the function and expression of potassium channels and excitability at the glutamatergic synapse (Wong et al., 2002). It may be involved in proteolysis and cell death (information inferred from http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P42658).

[132]Example 2. Molecular genetic screening of DPP6 in other brain neurodegenerative disease

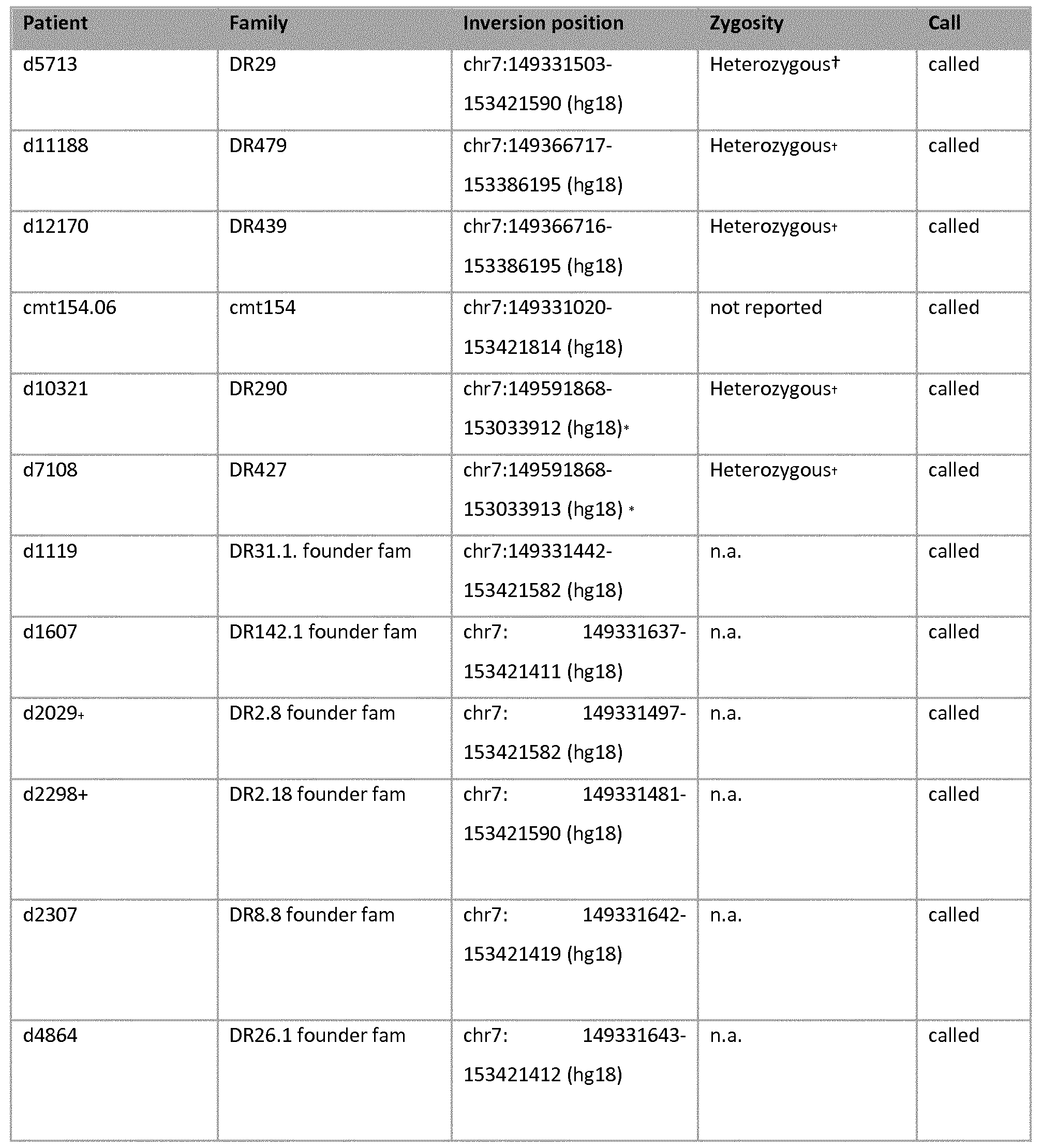

[133] To investigate the involvement of DPP6 in neurodegenerative brain diseases and estimate the frequency of this genomic rearrangement, we examined the 4Mb inversion locus in 137 additional genomes, of which 75 unrelated individuals, available in house in the frame of NGS projects on neurological conditions, and in 69 genomes of individuals without known NBD, released by Complete Genomics Inc. (http://www.completegenomics.com/public-data/69-Genomes/). This latter set consists of two trios, a 17-member CEPH pedigree and a diversity panel of 46 unrelated individuals from different ethnicities (52 unrelated genomes). The inversion was detected, with low reliability (3 reads), in one individual (NA12878) of the CEPH pedigree (frequency 1.9%). The in house available dataset contains genomes of individuals with different neurological phenotypes: 23 independent AD patients, 40 FTLD genomes, 8 independent PD/DLB genomes and 11 independent non-CNS neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. CMT, epilepsy). The DPP6 inversion, with breakpoint in the intron 1 of the gene, was observed in 3 unrelated FTLD patients (d5713, dlll88, dl2170), in 5 FTLD patients and 1 healthy at risk individual (d2029 - DR2.8), from 5 different branches of the GRN founder family (frequency in FTLD patients 20%) and in 1 young CMT patient (cmtl54.06), who, due to the young age at the last examination, might still develop dementia at older age (Table 5). Two additional FTLD patients (dl0321 and d7108) carried an inversion with breakpoint at the 5' of DPP6. It is unclear at present whether this interrupts a distant regulatory element (Table 5). The overall frequency of inversion in NBD, including the patients with potential breakpoint at the 5' of DPP6, is 12/71, 17%, which is significantly higher than in the set of unaffected individuals (1/52, 1.9%; RR 10.4 (95%CI 1.3-82.5), p-value 0.008. Further experiments including fluorescence in situ hybridization are ongoing to support and validate the presence of the inversion in these individuals.

[134] Table 5: The inversions identified in WGS. The zygosity is mentioned only if reported in the SV data, "n.a."= "not available"

[135] + these two individuals are members of the same branch, DR2, of the larger GRN founder pedigree and are children of affected brother and sister.

[136]† indicates that the zygosity was called with low reliability

[137] * indicates inversion with breakpoint in the 5' of DPP6

Haplotype sharing analysis for the inversion carriers

[138] The aim of this experiment was to examine whether the inversion carriers are sharing a common haplotype for the genomic inversion. For this purpose all the individuals who showed the genomic inversion in the WGS data have been genotyped using the same marker panel selected previously (Table 2), that in this particular case is including the DPP6 breakpoint (downstream or 3' breakpoint). In addition to these individuals we have genotyped the available members of the 3 Dutch families with the previously published haplotype sharing on chromosome 7q36 ( ademakers et al., 2005).

[139]Our data confirm the previous finding of the shared haplotype (D7S2439 (201bp), D7S798 (260bp) and/or D7S2546 (231bp)) between family 1270 and the three Dutch families 1034, 1104, and 1125. On the other hand this analysis did not identify a common haplotype between the potential inversion carriers. Notably, none of the WGS inversion carriers has the rare 260bp-allele for the marker D7S798. In conclusion, the impossibility to determine a shared haplotype for the WGS inversion carriers, might be explained by the fact that we are in a hotspot mutation region due to known genomic instability. This might indicate that the single genomic events are independent from each other without a genetic founder effect.

[140]WGS of 3 additional individuals of 3 Dutch families with shared haplotype with family 1270

[141] To further investigate the three Dutch families (1034, 1104, and 1125) with shared haplotype on 7q36, the WGS of 1 affected member, per family, was performed by Complete Genomics (CG), Inc. and all variations were called including the SV. Additionally the data were scanned with an in house tool to detect SV and in this specific case the inversion at 7q36. Neither the GC data nor the in house called data showed the inversion event. Currently it is not possible to exclude or confirm the presence of the inversion in the 3 Dutch families with haplotype sharing. Molecular genetic screening of DPP6

[142] Given the presence of complex genomic rearrangement in DPP6 gene in different NBD, we performed direct re-sequencing of the gene to evaluate the contribution of simple mutations in multiple NBD phenotypes (we screened 27 out of the 28 coding exons of the gene, exon 16 due to technical issues, has not been screened). Specifically, we screened 4 NBD cohorts. We prioritized from our extended cohort of AD patients a subcohort with an earlier onset age and we included in the screening the EOAD patients collected from the extended RotlOO cohort (Dermaut et al., 2003). We screened also our Belgian FTLD and ALS cohorts because of the reported association of DPP6 with ALS and the previously obtained clinical, pathological and genetic support for the existence of a FTLD-ALS disease continuum (e.g. C9orf72 repeat expansion mutations and TDP-43 pathology). Also, we do not have

neuropathology data for any of the Dutch AD families while in family 1270 some patients clearly have indications of a symptomatology involving behavior changes and frontal-temporal atrophy.

[143]Patient and control cohorts

[144]The Belgian AD subgroup consisted of 288 patients with an early onset age, mean age at onset (AAO) of 63.99 ± standard deviation (SD) of 6.58 yea rs (57.3% women) . Additionally we screened 82 EOAD patients from the Rotterdam cohort (RotlOO), AAO (±SD) of 56.99 ± 5.60 years (82.3% women). The Belgian frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) cohort consisted of 351 patients with a mean (± SD) age at onset of 62.44 ± 11.42 years (45% women).The Belgian ALS cohort consisted of 124 patients with mean AAO (±SD) 58.97 ± 11.91 years (39% women).

[145] The control cohort consisted of 408 neurologically healthy individuals with a mean (± SD) age at inclusion (AAI) of 72.56 ± 10.21 years (60.5% women). For exon 1 of isoform 1 an extra group of 423 control persons were screened, mean AAI (± SD) of 62.70 ± 13.38 years (53% women). Mutation spectrum and frequencies

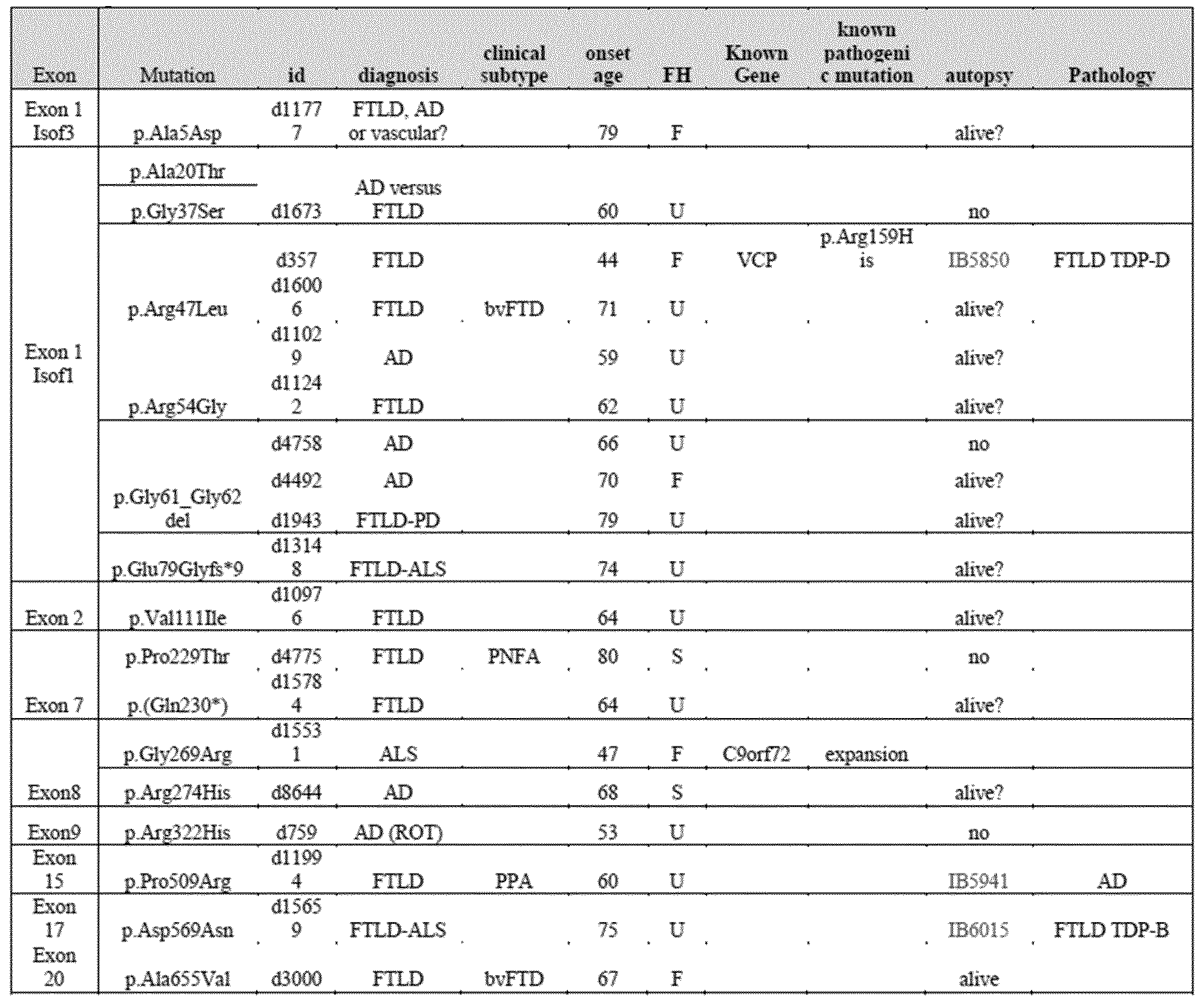

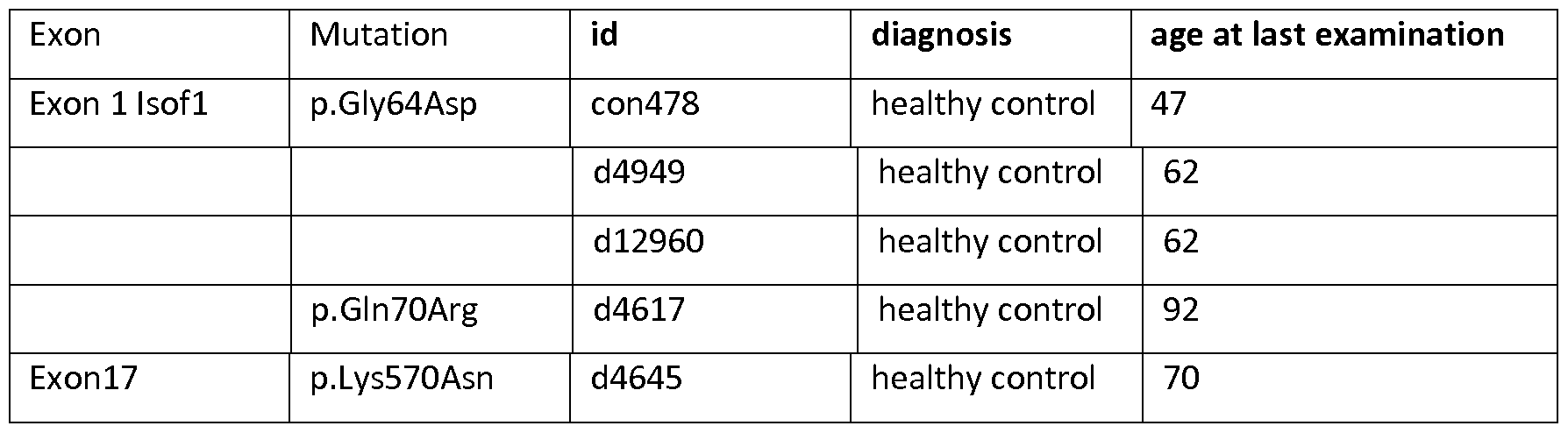

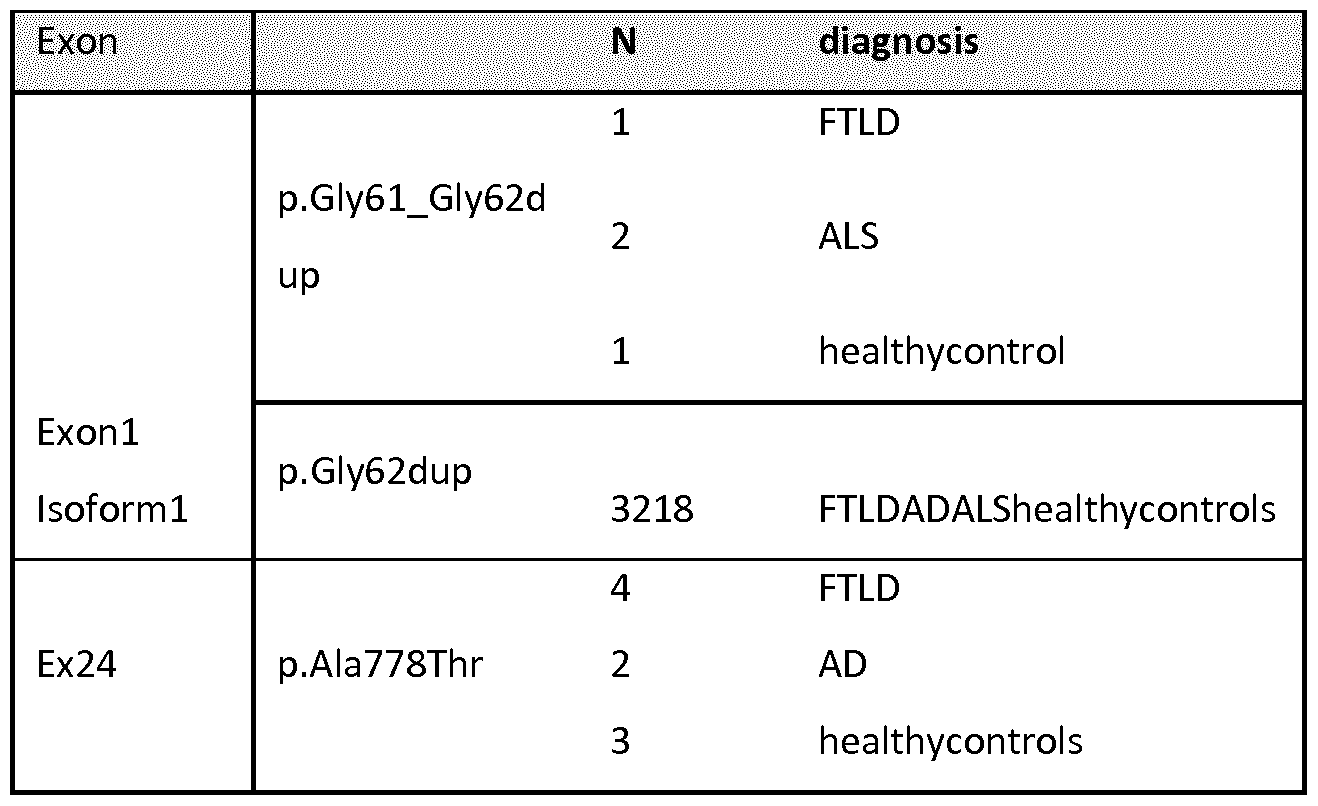

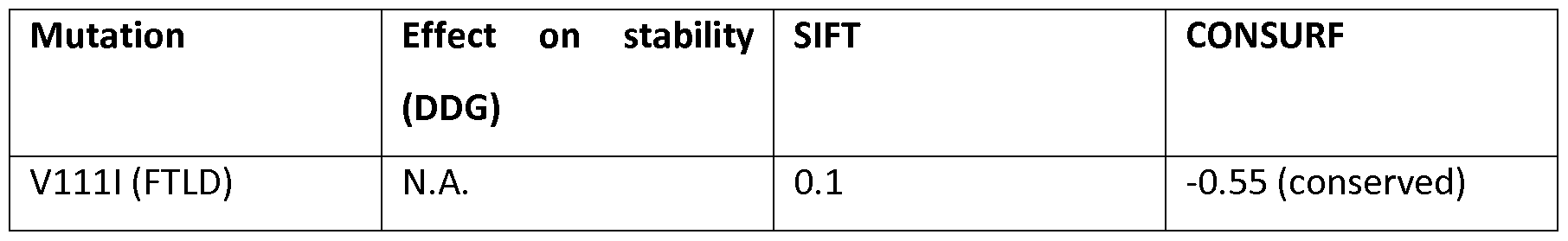

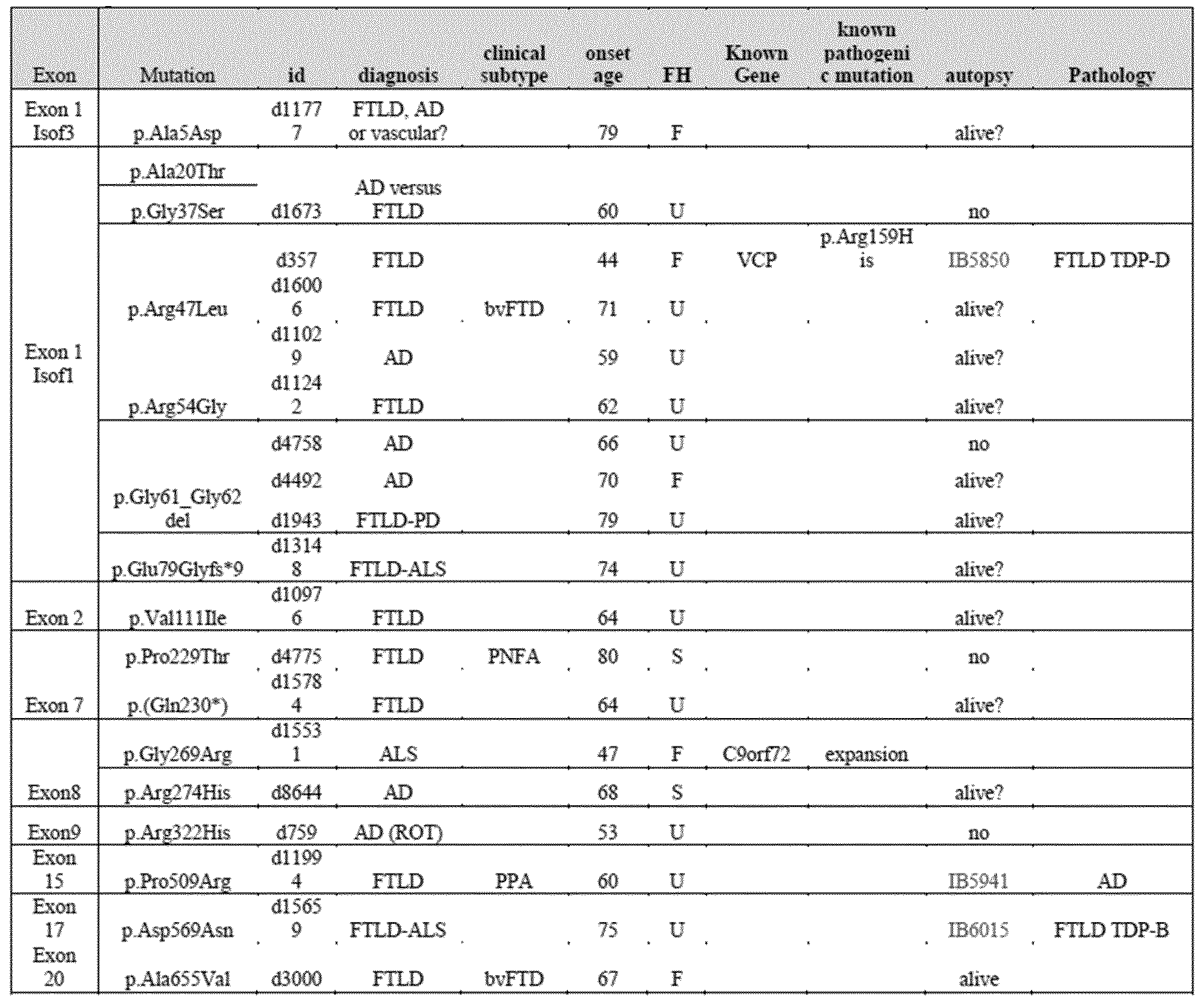

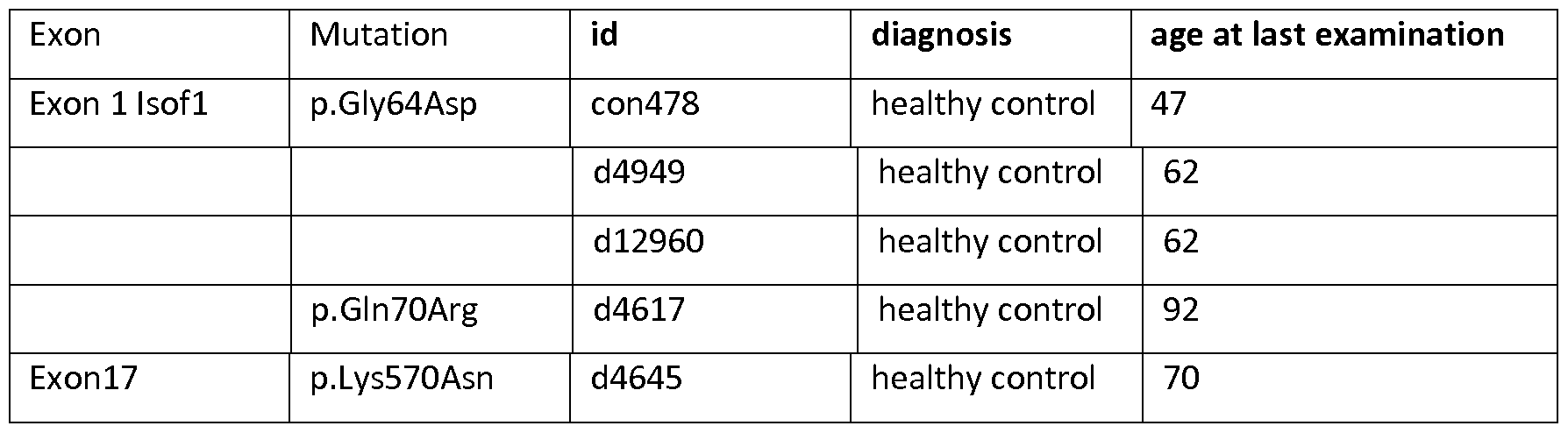

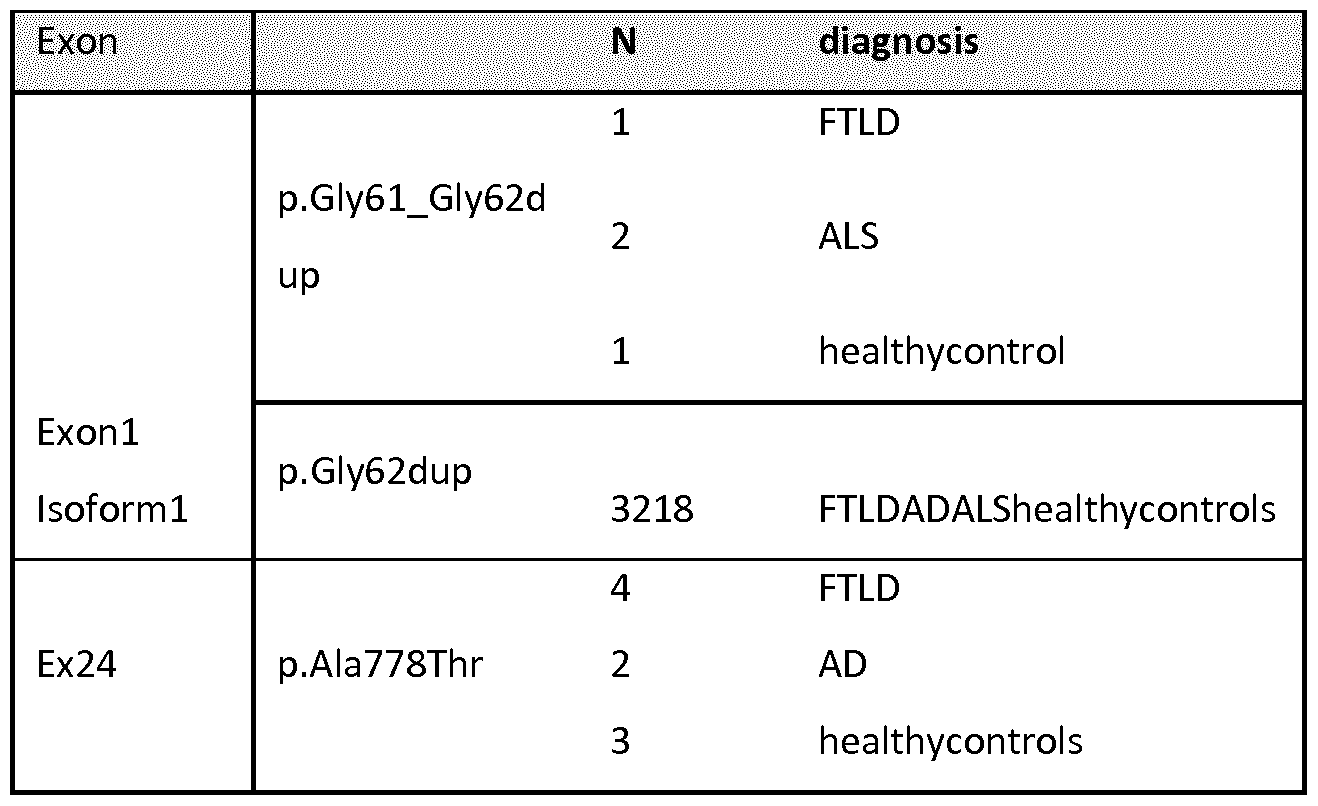

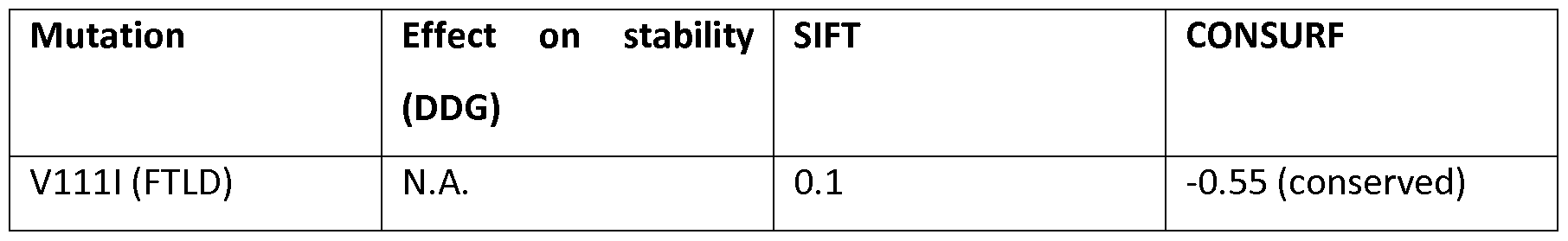

[146] In total 22 very rare (MAF <1%) non-synonymous variations were identified. Of which 16 in patients only (Table 6 and data not shown), 3 in control individuals only (Table 6 and data not shown) and 3 in patients and in control individuals (Table 6 and data not shown).

[147]In figure 8, the location of the very rare non-synonymous variations within the protein is visualized. The majority of the novel variations have been identified in FTLD patients. Of interest to note is that, for some patients, the clinical diagnosis was not clear (AD or FTLD) and for others a co-morbidity of ALS or PD was indicated. Also, when known, the majority of FTLD patients had a diagnosis of behavior variant of FTLD (bvFTD). Of 3 FTLD patients we have autopsied brain material available (IB-numbers). FTLD patient IB5850 carries a VCP mutation p.Argl59His and received a pathological diagnosis of FTLD TDP-D (van der Zee et al. 2009). Patient IB5941 with a clinical diagnosis of FTLD received a pathological diagnosis of AD but TDP-43 immunohistochemistry was not yet performed. Patient IB6015 had a clinical diagnosis of FTLD + ALS and a pathological diagnosis of FTLD-TDP type B.

[148] The mutation spectrum includes missense mutations, nonsense and frameshift mutations predicting premature stop codons, and amino acid deletions/duplications (indels). In control subjects only missense mutations have been identified. These are generally considered less deleterious than nonsense or frameshift mutations. The spectrum is consistent with a loss-of function either by affecting the protein structure and function (missense mutations and indels) or

loss of transcript by non-sense mediated mRNA decay (nonsense and frameshift mutations). Of note, several of the control individuals carrying a mutation are younger than the onset age of patients, so it remains a possibility that the mutations in these control individuals actually are deleterious.

[149]A) Patients specific

[150]

[151]B) Control individuals specific

[152] C) Patients and control indivi

C) Patients and control indivi

[153]

[154]Table 6: Clinical characteristics of carriers of the rare non-synonymous variants. FH = family history: "F" indicates positive family history; "U" indicates unknown family history and "S" indicates a sporadic patient. For the rare non-synonymous mutations identified in both patients and control individuals, only the total number (N) of carriers is reported. Panel A shows the variations exclusively identified in patients, panel B in control individuals only, and pa nel C in both patients and control individuals.

[155]The frequency of very rare variants was significantly increased in FTLD patients 20/351 (5.7%) compared to control individuals (0.98-1.56%) (p-value = 0.02, Table 7). We observed a similar trend in AD (3.47%) and ALS (4.03%), although this did not reach statistical significance (Table 7), likely due to the smaller cohorts.

[156] Total

Total

[158] Diagnosis in) carriers (n) Frequency {%) RR [95%Ci] p-value

[159] NBD 845 36 4.26 1.64[0.91 -2.96] 0.1

[160] Controls exllsofl 831 13 1.56

[163]Table 7: Overall frequency of rare non-synonymous coding variants in DPP6 (MAF <1%) in FTLD, AD, ALS and control individuals. Data are presented as counts and frequencies on the total number of individuals screened, Relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values are calculated after collapsing rare variant allele. A Mantel - Haenszel approach was used to compute RR and 95% CI, to take into account the different number of controls screened for exon 1 of isoform 1 versus the remainder of the gene.